Choose language:

Deepfakes: when technologies promote digital gender-based violence

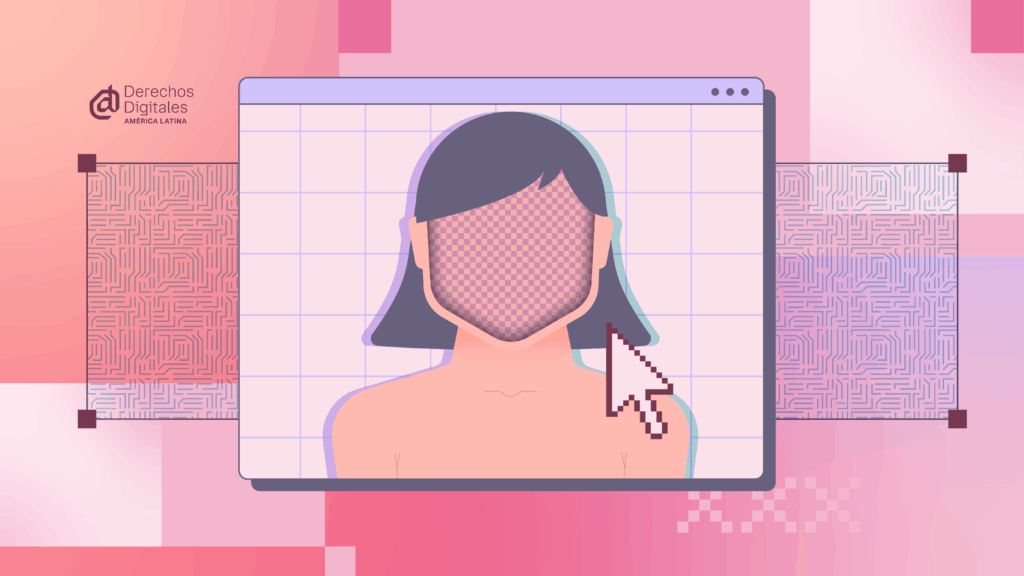

The increase in deepfake cases in Latin American schools is causing growing concern. An analysis of Android apps revealed a lack of transparency, embedded biases in their development, and a business model that prioritizes monetizing abuse. Far from being a “system error,” these tools were designed in ways that perpetuate digital gender-based violence.

Reports of deepfakes are increasingly common in Latin America. These technologies, based on artificial intelligence (AI), make it possible to create fake images by inserting a person’s face onto another person’s body, simulating situations that never happened -often of a sexual nature. In several countries across the region, particularly alarming cases have been reported in schools, where girls were victimized by their own classmates. These tools are commonly used to create, share, and even commercialize sexual content involving their female classmates. In recent years, the media have reported on such incidents, primarily in private schools in Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, and Guatemala, among others. Boys and adolescents are learning to exploit technology to abuse their female peers, while girls are left exposed to a form of violence for which no one has concrete answers.

As for media coverage, a pattern emerges: the most visible cases come from private schools in urban areas, but that does not mean they are the only ones. For example, a similar case occurred at a school in the Maule Region of Chile, in an area outside the major urban centers. Unlike the previous cases, this case is not easily found online, and it was the adolescent girls themselves who were forced to report it on social media.

In Latin America, where most schools do not belong to elites, what reaches the media represents only a fraction of reality. While some cases provoke outrage, many others are forgotten, and in contexts that are rendered invisible, victims receive no attention or institutional response.

In this column, we aim to analyze the role that deepfake applications are playing in Latin America in the spread of new forms of digital gender-based violence. Drawing on specialized studies and research, we examine the conditions that enable them and the technical, political, and economic responsibilities behind their operation, without overlooking the urgent challenges the region faces in addressing them.

Investigate the use of deepfake apps in Latin America

The cases reported in Latin American schools highlight a problem that goes beyond the technical. The emergence of these acts reflects a digital ecosystem that facilitates their spread without considering the consequences. According to the State of Deepfakes 2023 report, 98% of deepfake content available online has sexual purposes, and 99% of the people depicted are women. In addition, 48% of men surveyed have seen this type of content at least once, and 74% report feeling no guilt about it.

In response to this reality, research groups are taking note to produce scientific, accurate findings. Together with Situada, I conducted research to analyze the reach of these applications in the region, the conditions that enable them, and how their design facilitates digital gender-based violence.

To this end, we studied 105 deepfake applications published on Google Play (Android). These were identified using a tool specially developed for this purpose, which connected to the store via an API. This automated connection enabled us to collect technical and descriptive information for each app, allowing us to observe patterns in their design and functionality. While software analysis often focuses on usability, it is essential to evaluate this technology beyond its technical and commercial aspects, from an ethical, critical, and feminist perspective.

Red flag: the most concerning findings

Situada’s research found that 89.5% of deepfake applications pose a risk to women by facilitating the creation of non-consensual sexual content. The analysis revealed a worrying combination of socio-technical factors, reflected in the study’s main findings.

One of the first patterns identified was the lack of transparency in app development: 42.8% of the apps did not indicate their origin on Google Play or on their websites, making it difficult to hold them accountable and understand their motivations. Among those that did report authorship, sexualised promotional images were found that reinforce the objectification of women. Furthermore, a clear gender gap in the teams developing these apps highlights the persistent lack of diversity in the technology sector.

Men -particularly from the Global North- have historically dominated technological innovation, excluding women’s experiences and needs. This dynamic has been widely studied by feminist scholars who analyze how technological design and production reproduce structural inequalities. Among them, Judy Wajcman introduced key concepts in her book Technofeminism, where she explores how technological development is shaped by power relations. Recent reports by UNESCO and Randstad confirm that fewer than 30% of AI workers are women. This exclusion is not simply the result of a lack of access or skills, but of a masculinized technical culture that determines what is designed, for whom, and for what purpose.

Another critical aspect identified was the ratings of apps on Google Play. This store requires all apps to have an age label, assigned through a system managed by the International Age Rating Coalition (IARC). Developers are required to complete a self-declaration form and, based on their answers, the appropriate category is determined (e.g., “17+”). However, this mechanism relies entirely on the honesty of those publishing the apps. There is no active verification of the apps’ actual content. The analysis showed that 65.7% were rated as “Everyone,” despite being used to create non-consensual sexual content. Ratings that are meant to protect users end up legitimizing harmful technologies under misleading labels.

It was also evident that these tools operate under a business model focused on profitability. 67.6% require payment to unlock key features, and although some offer free trials, downloads are often restricted until payment is made, incentivizing purchase. This model prioritizes profitability over any ethical principle, facilitating the digital exploitation of women’s bodies. This is further compounded by their ease of use: 96.2% were rated as intuitive, even accessible to people without technical experience or language proficiency, which broadens their adoption.

Furthermore, the analysis showed that these online services include features that simulate kisses or hugs, normalizing the idea that women can be exposed in intimate situations without their consent. In the advertisements for these apps, it is common to see forced representations, almost always featuring a man using his own photo alongside an image of a woman, reinforcing dynamics of control. Additionally, the use of predefined templates contributes to their hypersexualization: female options abound in categories such as “Hot Bikini,” “Latex,” “Sexy Girl,” or “Body Latino” (reinforcing fetishized stereotypes of Latina women), while male templates are scarce and neutral.

Finally, the companies behind these applications avoid legal liability through disclaimers that prohibit the use of unauthorized material, while leaving execution entirely in the user’s hands. This finding shows that the legal strategy does not prevent harm, but it does protect the companies that profit financially from these practices. By shifting the moral burden solely onto the user, these companies evade their ethical responsibility as designers of technology with foreseeable impacts.

A global trend reflected in Latin America

The conclusions of this research fit within a global trend, of which Latin America is no exception. Several civil society organizations have warned that technologies such as deepfakes are part of a growing wave of digital gender-based violence. In a recent report submitted to the UN, Derechos Digitales, along with other groups, highlighted that these practices silence voices and limit public participation.

Along the same lines, Coding Rights has documented how certain AI-based services impose patriarchal and colonial visions on the bodies and decisions of girls and adolescents in our region. Similarly, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) has raised alerts about the use of deepfakes for extortion and sexual humiliation, warning about the lack of regional policies to address this problem.

From the legal standpoint, after compiling cases of deepfake porn, activists such as Olimpia Coral stress that “the law is insufficient” and that it is urgent to train police officers and prosecutors to understand these technologies and properly assist victims. The evidence is also apparent in the political arena. A study by Fundación Karisma, in collaboration with UN Women, focused on the 2022 legislative elections, concluded that information manipulation -including deepfake images and identity impersonation- has become a form of digital violence against women candidates.

Taken together, these reports align with what Situada’s research shows at the regional level: AI technologies, when developed without ethical accountability and public oversight, reproduce historical forms of violence against women.

False neutrality: technologies that perpetuate gender-based violence

The results of these analyses are alarming, but they pale in comparison to the impact on the women affected. While these apps generate profit, women and girls see their images manipulated and circulated without their consent. Some fear leaving their homes, others experience anxiety and depression, or are extorted and revictimized by those who downplay the harm with excuses such as “it’s just AI” or “it’s not real,” ignoring that online actions have real-life consequences.

This widespread proliferation cannot be separated from a connectivity-driven economy that rewards virality and turns exposure into capital. The number of downloads legitimizes these practices as acceptable, while rendering their harmful impacts invisible. What occurs in this digital marketplace is an extension of patriarchal logic that treats women’s bodies as objects for others’ desire. It is a structural form of violence that reduces women to sexual objects and erases their agency in the service of male pleasure.

Platforms such as Google Play legitimize this ecosystem by allowing the widespread circulation of technologies that enable symbolic and sexual assaults without consent, under profitable commercial schemes. Holding users solely responsible is insufficient. It is necessary to question the technical, economic, and regulatory systems that enable these forms of violence.

The challenge is not only to denounce these practices, but to rethink technology from its roots: to recognize that every tool involves moral and political decisions. Addressing this problem requires coordinated responses, including gender-focused regulations that compel platforms to remove non-consensual content, and corporate transparency commitments that incorporate ethical impact assessments before releasing tools that could be used to cause harm. It is also necessary to advance comprehensive reparations measures for victims, including psychosocial support, legal assistance, and guarantees of non-repetition. Finally, promoting critical digital literacy -especially among young people – can prevent these violent uses and build a digital culture based on respect and consent. Moving toward public policies with an intersectional feminist perspective and ethical development practices is urgent to ensure that innovation is not built at the expense of people’s dignity.