Choose language:

Tech giants in the agri-food chain: corporate concentration and deepening peasant dependency

The digitalization of agriculture is already a fact: Big Tech companies are working alongside monopolistic agribusiness corporations, driving an unprecedented datification in the rural sector. Peasant and indigenous communities are demanding protection and security over their knowledge, data, and modes of production. Is it possible to introduce digital technologies in rural areas in ways that respect peasant rights and promote food sovereignty?

Food prices worldwide increase day by day. Beyond specific contexts, such as wars or natural disasters, we can easily identify the main driver of food inflation: monopolistic control by agribusiness corporations.

As Big Tech penetrates almost every sphere of life, the food production chain is no exception, and may even aggravate the situation. Alliances between agribusiness giants (Bayer, Syngenta, Cargill, for example) and technology giants (Google, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, among others) are raising concerns, especially among peasant and Indigenous communities. Recent research warns of deepening dependency, the commodification of collective ancestral knowledge, and a possible intensification of environmental contamination. In the following sections, we examine the impacts of this digitalization of agriculture on peasant rights.

Giants of digitalized agribusiness

Corporate concentration in agriculture comes as no surprise: oligopolies already dominate the global food chain. These companies control everything from genetically modified seeds to so-called agricultural inputs: pesticides and fertilizers for monocultures, which remain unsustainable due to their environmental impact and soil degradation. This system directly affects peasant production methods, which underpin food production in our region.

This industry has now entered a new phase. A new report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food finds that agrifood corporations are turning to digital technologies and large-scale data processing. This trend, driven by digitalization, creates new human rights challenges in food systems. The ETC Group’s latest report describes it as “Trojan horses on the farm”: technology and innovation promise benefits, but hide greater corporate control and less autonomy for farming communities.

Accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, the digitalization of agriculture is being promoted by transnational corporations in the sector as a solution to certain climate change problems and as an inevitable transformation toward a more efficient production model, as the World Bank has argued for years. With all this hype and marketing, digital agriculture startups (“AgriTech” in their terms) are flourishing in the region, with Argentina and Brazil hosting almost three-quarters of these companies.

The bot seed in the fields

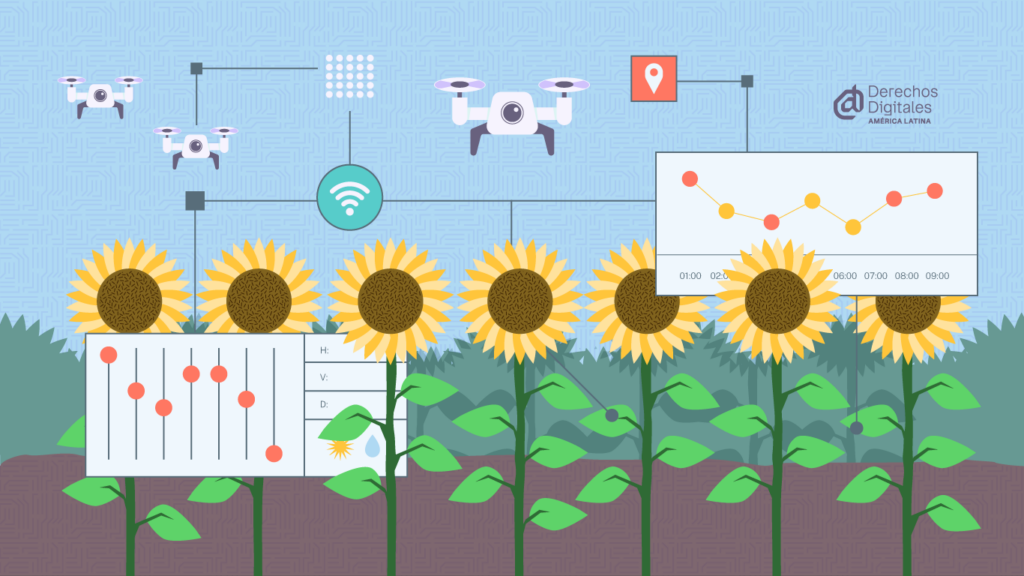

The presence of drones in the skies, sensors in the soil, and GPS-guided tractors is no longer unusual. Producers now use tablets and devices with specific applications and systems. Digitalization in agriculture means people widely use tools such as AI, data science, and biotechnology to map land, store information, and create new digital systems that manage rural production methods.

The alliance between Big Tech and monopolistic agribusiness corporations is promoting an unprecedented datafication of knowledge related to agriculture and the behavior of ecosystems and common natural resources. This represents a massive data extractivism which, in many cases, is linked to community and collective histories and traditions. Those with the greatest capacity to collect and control them will be the ones who can shape food systems and agricultural policies for their own benefit, a business market that does not consider food to be a human right, and much less acknowledges the existence of peasant rights. It is not about abstractly questioning the introduction of new technologies, but rather asking whose interests they serve, who controls them, what production models they reinforce, and how the data is handled.

Let us review some of the main risks of this process. Subscribing to a production system managed through a digital platform implies an even greater dependency for farmers: it becomes a circuit in which everything – from the decision on which seed to plant to the payment and collection system – must go through virtual services. The UN Rapporteur makes it clear: “In these new digital factory farms, farmers are no longer self -determined agents and instead are objects of harvest.” As in most platform-regulated jobs, there are no clear, transparent rules on data use or strong privacy policies, resulting not only in the exploitation of such data for mercantile purposes but also in the enabling of new control practices, which some groups refer to as “surveillance agriculture”. Considering that Latin America is one of the most hostile regions for environmental defenders, this form of surveillance is particularly concerning.

Moreover, in a region with a significant digital divide, where many of our countries face the highest mobile internet rates in the world, access to the network imposes new expenses for communities, worsening their living conditions in their territories. Even more so if we consider the high costs of smart machinery. In addition, according to the ETC report’s findings, millions of jobs in the field are expected to be replaced by drones and robots, without planning for new sources of employment in the sector. In some countries, farmers are even prohibited from repairing their machinery because it contains patented software. Finally, as we have already pointed out in Derechos Digitales, the enormous demand for natural resources, such as water and energy, to power all the digital infrastructure needed for these ventures, is likely to lead to higher levels of pollution and a deepening of the climate crisis.

Big data in agriculture thus becomes a tool of dependency, surveillance, and control that puts peasant autonomy and agricultural biodiversity at risk.

Let’s get the technologies unwired!

“The world does not need more data or more food – people instead need more power and control over data in food systems,” warns the UN. As mentioned above, we are not questioning the incorporation of digital technologies, but rather the way they are used and the models they support. Peasant communities can favorably use technological tools that contribute to the common good instead of profits concentrated in a few hands. Many are already experimenting with this!

Organizations that comprehensively plan alternative agri-food models from their territories consider each stage of the cycle: from the moment food is sown (its inputs, labor, etc.) until it reaches people’s plates at home (trade, transportation, etc.). There is a widely used phrase that sums up this proposal very well: “From farm to table.” Therefore, the experiences of collectives linked to rural work, environmental defense, Indigenous communities, and digital rights can encompass different links in this mode of production, grounded in the principles of Agroecology and Food sovereignty.

The Territórios Livres, Tecnologias Livres (Free Territories, Free Technologies) project, promoted by Intervozes together with quilombola and rural communities in Brazil, set an interesting precedent in analyzing the uses and conceptions of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in peasant territories. Similarly, the Latin American Network for the Assessment of Technologies (Red TECLA) brings together several projects focused on agriculture. The People’s Monitoring Tool for the Right to Food, a project of the Global Network for the Right to Food and Nutrition, aims to guide communities, movements, civil society, academics, and even civil servants in monitoring the human right to adequate food and nutrition. In addition, the Grassroots Innovations Assembly for Agroecology (GIAA) is a global network that is strengthening experiences with grassroots technologies applied to agroecology.

If we think about the production chain, there are developments directly linked to sowing and cultivation stages, such as the Lunagro application (FIAN Colombia), an agricultural calendar based on the interpretation of the lunar cycle. Also, La Mierda de Vaca offers both in-person and online courses on how to practice organic agriculture.

Both the isolation and preventive distancing imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as the discussions it sparked about healthy eating, led to an exponential increase in demand for organic or agroecological vegetables. In Argentina, Más Cerca es Más Justo, and in Brazil, Alimento de Origem, are examples of the dozens of platforms belonging to fair trade networks in Latin America, seeking new forms of exchange, avoiding intermediaries and overpricing, and connecting producers and consumers more closely.

To leverage satellite imagery for the benefit of local production and the conservation of natural commons, many organizations are working with Organic Maps, a privacy-centered, offline GPS and mapping application developed by the open-source community. There are also numerous projects that bring together activism, academia, and communities, such as Water governance in collaboration with a Yaqui Tribe community in Mexico, analyzed in our Glimpse 2024, designed to develop effective strategies for community-based water management.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the importance of information and debate sites that advance these movements’ agendas and promote the dissemination of ideas related to alternative food systems. Among them are Agro é Fogo, which disseminates “the fire trail of global agribusiness”; BiodiversidadLA, developed by the Latin American Coordinator of Rural Organizations – Vía Campesina; and Agencia Tierra Viva, promoted by the Argentine Agri-Food Table, among many other regional initiatives.

Food and digital sovereignty for a better life

The challenges posed by digitalization in the rural sector are varied and complex. While digital technologies are promoted by civil society and the state for the benefit of communities and territories, it is essential to establish national, regional, and global regulatory frameworks that can protect privacy and data from corporations driving the datification of the rural sector. A few years ago, the State of Brazil designed the Cadastro Ambiental Rural (CAR) as a tool that could be useful for monitoring the environment and territories, leading to a highly relevant debate from Data Privacy in relation to the personal data of community members. Some sectors have even proposed treating food system data as a public good to address this issue. It is necessary to recognize and protect the traditional knowledge of the peasant community, as well as their collective rights, in order to strengthen technological tools that respect these particularities.

Given the complexity of the issue and the giants involved, we need to refine our analyses and, above all, foster connections between the digital rights movement and peasant and indigenous organizations in order to provide comprehensive responses. For example, a few years ago, IT for Change published the report “The digital ecosystem opportunity for Indian agriculture” following a series of discussions and exchanges among various actors involved in these matters.

We can discuss digitalization, datification, how data is obtained, where it is stored, and who controls it, but if we do not address the radical questions about our ways of life and food, we are likely to get lost along the way. Why do we need digital technologies in agri-food systems? What role do peasant and Indigenous communities have in defining these new tools to be incorporated into production methods? What models prioritize food and digital sovereignty, and peasant and Indigenous communities’ rights to self-determination?

What is at stake is not only access to new technologies and data protection, but mainly the food sovereignty of the people and the human right to decide how to produce and consume our food in a fair and sustainable way.